Some fear that romances might give readers unrealistic expectations about relationships and unhealthy attitudes about sex, a theory posited by relationship psychologist Susan Quilliam in a July essay in the Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care.

To be fair, one could equally well say that there's only a "handful of anecdotes" supporting the idea that romances are good for you (albeit a large handful). It might be interesting to know whether Burnett and Beto's findings would be replicated across larger groups of romance readers (they only interviewed "15 [...] women between the ages of 18 and 55"), because they found mixed effects:Not so, says Eric Selinger, associate professor of English at DePaul University, who uses romances in his research on love, desire and literary pleasure. "Every year or two someone sends up a warning flare: 'Reading romance is bad for you!' There's no … data, no evidence — just a handful of anecdotes."

The women agreed with Alberts' (1986) findings that the fictional conversations in romance novels inform and reflect the actual male-female conversations of the social world. One participant described how she used the communication in the novels to help her "communicate with the people around [her]." Some of the participants explained that they were able to have the right expectations of their romantic partners, but one participant explained that she "sometimes compares" her husband with the hero, which "flusters" him. Other influences of the romance novels include a change in their mood because "it helps you kind of get yourself out of the context of whatever is going on." A couple of the participants explained that romance novels help you to communicate better with your romantic partner, partly because the novels give "a guy's point of view." The comments stating that conflict was handled similarly to that in romance novels were divided almost equally between "yes" and "no." [...]

The final question asked during each focus group was if the participants thought that romance novels have had an impact on their relationships. They explained that there were some comparisons in their relationships to those in the novels, but even when there was not, they still stayed committed to their "real life" partners. However, two of the women said that they now knew why some of their relationships did not work out--because they were not "looking for real substance." They were "looking for the fairy tale romance novel."The whole of that study is available here. Regarding the question of whether fictions are good or bad for us, Robert Sternberg argues that

All our lives we have heard stories of various kinds, many with love as a leitmotif. We thus have an array of stories we can draw on when composing our own. (26)

We come to relationships with many preconceived ideas. These ideas, or stories, are not right or wrong in themselves, although they may be more or less adaptive - that is, more or less healthy in promoting a good fit to the environment. What is viewed as adaptive varies over time and place. For example, one culture might view love as an indispensable part of marriage; another culture might view love as irrelevant to marriage. In both cultures, these values are likely to be taught not as somewhat arbitrary matters of cultural convention, but as matters of right and wrong. What are viewed as "realities" are rather perceptions of realities - stories. (7)

stories are so powerful in our lives, and also so hard to change. We may continue in a relationship that is dysfunctional in many respects simply because it does represent love to us, "sick" as that love may seem to others. We may even see the culture as supporting the kind of love we have. (221)

|

| Tristan and Isolde - adulterous love |

|

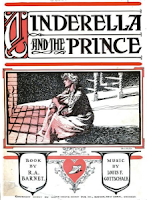

| Cinderella waiting for her Prince |

--------

Burnett, Ann, & Rhea Reinhardt Beto, 2000. ‘Reading Romance Novels: An Application of Parasocial Relationship Theory’, North Dakota Journal of Speech & Theatre, 13.

Lamb, Joyce. "Readers' hearts remain true to romance novels." USA TODAY, 14 February 2012. [Edited to add: A fuller version of Eric's thoughts on the benefits of reading romance can be found at the end of another post, on the USA Today's Happy Ever After blog.]

Sternberg, Robert. Love is a Story: A New Theory of Relationships. New York: Oxford UP, 1998.

The first image is of John William Waterhouse's "Tristan and Isolde with the Potion" and the second is of the cover of Louis Ferdinand Gottschalk, David Kilburn Stevens, Edward Warren Corliss and Robert Ayres Barnet's Cinderella and the Prince; or, Castle of Heart's Desire: A fairy Excuse for Songs and Dances. Boston: White-Smitz music pub. co., 1904. Both came from Wikimedia Commons.

Laura: I'll read the study in total, but is there any reference to why they're focusing on Romance novels and not, say, Disney fairy tales or romantic comedy films or other cultural productions that push the fairy tale romantic line?

ReplyDeleteI didn't start reading Romance novels until adulthood (and I'm including the massive quantity of popular women's fiction I consumed in grad school), so I got that fairy tale conditioning elsewhere. And I certainly had imbibed more than a bit of it, some of it unconsciously.

Also, have you seen this Scientific American article on the positive social and personal effects of reading fiction: http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=in-the-minds-of-others

"is there any reference to why they're focusing on Romance novels and not, say, Disney fairy tales or romantic comedy films or other cultural productions that push the fairy tale romantic line?"

ReplyDeleteAs far as I can tell, they chose to focus on romance-reading because (a) they wanted to investigate "parasocial relationships" and (b) "The effects of parasocial relationships, or PSRs, have been studied in many genres, including television programs, news, soap operas, and home shopping shows" but "while parasocial relationships have been studied with other forms of mass media, the possibility that romance novels can be a source of parasocial relationships has never been studied. Similarities exist between the medium, however."

I got that fairy tale conditioning elsewhere. And I certainly had imbibed more than a bit of it, some of it unconsciously.

Yes, that's what Sternberg's suggesting - that we can get these stories from a variety of places. That's why I illustrated the post with pictures of Cinderella, Tristan and Isolde: people don't get their ideas about romance solely from romance novels and many people don't get them from romances at all.

Also, have you seen this Scientific American article on the positive social and personal effects of reading fiction

No, but I've read other things by Keith Oatley. He's one of the main contributors at OnFiction and I would have read more of his latest book, Such Stuff as Dreams but I took a very quick look through it and as I mentioned in this post he doesn't seem to ascribe the same benefits to reading genre fictions as he does to reading literature which he'd classify as "art."

I have not read Oatley's book, either, but I'm curious about it, particularly about some of the differences he posits. I'm more drawn to the "skills" argument than the "values" argument when it comes to the effects of reading, I think.

ReplyDeleteI have come to realize how deeply skeptical I am about the shift from anecdotal to theoretical treatments of reader responses, in part because I've been subject to too much bad reader response theory, and in part because I'm inherently suspicious of the application of various social sciences to the relationship between specific types of media and individual consumers.

I've probably just read too much bad stuff without a nuanced approach to the way cultural products mirror, interpret, are interpreted, etc. So if anyone has a recommendation for a great study, I'd love to hear it.

"I've been subject to too much bad reader response theory"

ReplyDeleteWould that include Radway? I don't know much about reader response theory at all, but I did find many of her generalisations about romance readers very irksome.

"if anyone has a recommendation for a great study, I'd love to hear it"

I don't, and I'm about to go off at a bit of a tangent, but after reading Sarah Wendell's EIKAL, in which she writes that

You don't see adult gamers being accused of an inability to discern when one is a human driving a real car and when one is a yellow dinosaur driving a Mario Kart, but romance readers hear about their unrealistic expectations of men almost constantly (6)

I thought about this:

Some video gamers are so immersed in their virtual world they end up trying to use gaming experiences in real life, according to researchers.

A study spoke to 15 to 21-year-olds and discovered some gamers end up doing things like reaching for a search button to find someone in a real crowd.

Others had tried to use a 'gravity gun' to pick up food.

Almost all of the 42 people questioned reported some type of Games Transfer Phenomena (GTP) to varying degrees.

Half of those questioned said they often try to resolve real life issues using something from a game.

Professor Mark Griffiths, one of the report's authors at Nottingham Trent University said intensive gaming may lead to psychological and emotional problems adding that there will be "enormous implications for software developers, parents, policy makers and mental health professionals."

The research will be followed up with a study of a much larger number of gamers. (BBC)

Sigh, I wish people would walk away from the car-crash that is Quilliam's contribution to this debate.

ReplyDeleteBut check out the really interesting essay on the Awl about romance: http://www.theawl.com/2012/02/romance-novels.

Dear Author linked to this on Valentines Day, and I thought it was one of the best defenses of the genre I've encountered.

Thanks, Sprout!

ReplyDeleteI've read that post at The Awl several times now but I still can't understand its appeal. I think that may be because although I, too, have enjoyed many of the "Golden Age" romances, I prefer the ones which are not "crazy as hell, glittering with imagination and lunacy." Or, to put it another way, I'd much rather read Mary Burchell than Violet Winspear. And, while I don't disagree with the quote from jay Dixon about how in romance "Men have to be taught how to love; women are born with the innate ability to love" (indeed, that pretty much sums up why the GlitteryHooHa and the Prism have to transform the Mighty Wang and Phallus) that isn't the kind of romance I prefer.

So as a result, the emotional experience that Bustillos describes isn't really the one I have when I enjoy a romance.

Laura:

ReplyDeleteThat gamer study excerpt reminds me more of reflex memory or something like it. When I switched over from a manual transmission car to an automatic, for example, it took me the longest time to NOT reach my left foot out for the clutch all the time. I knew, of course, that I wasn't in my old car, but it took a while for me to change the reflex. Depending on how much time someone spends gaming, could the effect be similar, even though someone knows it's not a game they're in the midst of? I think Wendell's point, too, is that certain hobbies that are associated with men tend to get less ridicule than those associated with women, especially when it comes to questions of intellectual rigor and general mental and emotional strength.

As for the reader response question you asked, that definitely includes (but is not limited to) Radway. ;D

I've been thinking about the reactions to games/fictions and it seems to me that, to steal a favourite quote of Jonathan's, romance seems to be stuck in a difficult position, simultaneously "too little and too much": too much for some people (who fear it will affect readers too much) and not enough for those who wish that romance would offer a comprehensive programme of action to be taken against patriarchy.

ReplyDeleteThe article at the Awl that Sprout linked to, in conjunction with Liz McC's post about emotional reading and my own negative reaction to the Awl post, makes me thing there's a similar "too much and too little" issue at work there, too.

Like Robin I am dubious about any attempt to generalize about readers and the effects of their reading on them. (I'm interested in thinking about my personal experience of this, but even a short conversation with other readers quickly reminds me my experience isn't universal). I do often see comments around Romanceland about "oh, readers want X," (to fall in love with the hero, we only care about good storytelling) and it often doesn't apply to me. There's a lot of over-generalizing about readers.

ReplyDeleteI had that issue with the Awl piece. It worked for me as one reader's reflection her experience reading a particular kind of romance. On that level, I thought it was thoughtful and beautifully written. But it was also "too much" in the sense that its generalizations (about romance, about feminism) failed for me. I don't particularly enjoy the type of romance Bustillos talked about and don't read the way she does either. Yet she seemed at times to be saying "all romance is like this."

The particular narrative she discusses--women are born knowing how to love, men have to learn; men are domesticated, tamed, brought within the world of love and home--is common but not universal. And I'm glad, because I'm tired of it (I do enjoy it sometimes, but wouldn't want it to be the only story romance offered me). It is very gender stereotypical, and at times I see it as an insult to all the real men I know who wanted love and family in their lives from the start and did not need domesticating.

There's another way the too much/too little works. When I find myself generalizing that romance is "too little" I remember that it is only one genre; it's not fair to expect "too much" from it; it can't satisfy all my reading desires. So I turn to other books for awhile. At the same time, I think there is a tendency to expect "too little" from romance. I am amazed at the poor editing of all kinds, for instance, that we readers will put up with in our desire for a satisfying story. We deserve more from the genre we love (now I am way off topic...).

I do often see comments around Romanceland about "oh, readers want X," (to fall in love with the hero, we only care about good storytelling) and it often doesn't apply to me. There's a lot of over-generalizing about readers.

ReplyDeleteIt doesn't apply to me either, and reading a lot of comments like that generally makes me feel that I'm odd/not really part of the community. It's not dissimilar to comments like "Oh, all women love buying shoes!" which tend to make me think "and ain't I a woman?" except it's worse, because I know a range of women and so can more easily recognise those generalisations for what they are, whereas with romance I feel more marginalised anyway, given how infrequently the novels that others love are the ones I love (and vice versa).

now I am way off topic..

But that's often when things get interesting!

it's not fair to expect "too much" from it; it can't satisfy all my reading desires. [...] At the same time, I think there is a tendency to expect "too little" from romance. I am amazed at the poor editing of all kinds, for instance, that we readers will put up with

I wonder if the academics who've criticised romance for not being enough did so at least partly because they had great hopes for what a genre mostly written by women, for women could be?

And maybe those who're wary/hostile to academic criticism of the genre and/or are happy to put up with poor editing, fear that too much political correctness/attention to detail will inhibit the "too much" qualities that they value?

The 'too much v too little' model is interesting. I have lately been thinking of these issues from a different angle, namely in terms of those who speak on behalf of the genre, where I see a dilemma of 'all things for all readers.'

ReplyDeleteIn other words, it seems to me that there's desire to have the people who speak publicly about the genre (and the larger the platform, the larger the expectation) to represent what the "readers" think. And when someone speaks about the genre and they do not speak for YOU (general you) in all ways, then is there a sense of illegitimacy?

I have fallen into this particular trap myself, especially when the primary public face of Romance seemed to be that of mantitty and dressing up as characters, etc. It's one reason I've been so grateful for some of the more recent public spokespeople, like Sarah Wendell, for example, who IMO has provided a smart, sophisticated representation of the genre and its readers, and has helped open the door to more positive and respectful mainstream attention as well as, perhaps, less shame in expressing public love for the genre (e.g. that Awl piece).

So when I started to see backlash against people like Wendell, it got me thinking about whether there would be ANY perfect spokesperson for the genre. IMO there would not be, because no one person speaks for everyone, and no two people will be in accord on every single idea and belief. But I think it can be tough to feel that those who are speaking publicly aren't speaking for (figurative) us, especially on behalf of a genre that's already getting so much flack.

And maybe it's the same for the genre. In one sense it's far too large for the generalizations any of us make about it, and yet there's an element of generalization in any claim one can make. And when those generalizations don't speak for our experience of the genre, it seems like there's a disconnect, and it creates frustration.

I also think it's a bit of a catch-22, especially for those who also study the genre. When you study a genre you don't really read much of, you can miss the particularities of its paradigm, but when you study a genre you read and like, you can feel a personal attachment to the work that deepens the intellectual investment (which in turn can intensify the personal). And when the genre in question has historically been marginalized, academically and culturally, the dynamic is even more complicated and fraught.

And when someone speaks about the genre and they do not speak for YOU (general you) in all ways, then is there a sense of illegitimacy?

ReplyDeleteThings can certainly get heated. As far as I can recall, there were quite a lot of people who resented the way in which the Romantic Times conferences, with their male cover-model competitions, were given extensive coverage in the press. I assume that's what you're referring to when you write that "the primary public face of Romance seemed to be that of mantitty and dressing up as characters, etc." Conversely, weren't some rather pointed comments made by Michelle Buonfiglio (who was more on the pro-mantitty and rape-fantasy side of the romance community) about Sarah Wendell at the Princeton romance conference?

I wonder if, in the US, the debate about romance is much more focused on sex, even when readers differ about how or by whom they'd like that to be expressed (i.e. Sarah Wendell argues that romance is sex-positive, Buonfiglio argued that it gave readers a place where they could explore their sexual fantasies). I have the impression that in the UK the divide seems to have been between Barbara Cartland and the other romantic novelists who wanted their writing to be taken seriously.

This isn't, I think, because UK readers or authors are shy about sex. Rather, I wonder if sex is a much more controversial issue in the US than it is in the UK (that's the impression I'm getting from reading about US abstinence-only education and the controversies about contraception and abortion provision).

LOL! Buonfiglio was one of the people who came to mind when I was writing that. And the snide comments directed at Sarah Wendell were so interesting, because IMO they went against everything she claimed she was supporting in more "serious" attention to the genre.

ReplyDeleteI think it's easier for me to take the pro-mantitty image of Romance and its readership when people like Wendell and others are propagating a different image. I know there's not a single person who speaks for me/with whom I agree all the time, but I'm philosophically more aligned with some representations than others.

Regardless, I don't think there's ever going to be one "perfect" spokesperson, although for me, the more respectful attention the community gets through mega-popular sites like SBTB, the more it will allow for a diversity of images of the genre and its readers, and maybe that's really the ideal.

As for sex, I definitely think the rampant conflicted moralism in the US has created some of the issues. However, I've also seen more than a few genre readers diminish the value of the genre, describing it as un-serious, focusing vocally on hot cover models, and trivializing their own enjoyment of Romance. Some of this might be a defensive reaction, but I also think it's enabled those who already have negative perceptions of a genre that takes seriously the softer emotions and contains explicit sex.

My point about the US/UK comparison was that as far as I can recall, when romances are denigrated in the UK it's usually because they're being described as unrealistic/badly-written/soppy/heteronormative. I don't think there are the same anxieties about their sexual contents, and when those are critiqued, it's probably because of worries about inaccuracies (e.g. Quilliam was concerned about the lack of condom-use in romances). If anything, most people probably think (rightly or wrongly) that the sexual content in Mills & Boons is pretty tame.

ReplyDeleteI think it's easier for me to take the pro-mantitty image of Romance and its readership when people like Wendell and others are propagating a different image

To me, Wendell's image doesn't really seem very different from the pro-mantitty image: both are prioritising the importance of sex in romance novels. Obviously Wendell does discuss how romances can help readers in a variety of ways which are not related to their sex-lives, but all the same, the importance of the sexual aspect of romances is something that she emphasises:

Romance novels [...] offer safe spaces of sexual exploration and, to be honest, research on what it means to be intimate. [...] Sexual depictions in romances are also mostly positive and affirming [...].

Reading about passionate sex and sex as a method to express emotional passion has two benefits. First, you get to think about, or mentally try out, acts that you're curious about without actually doing them [...].

Second, you are able to read and learn in privacy. Let's be honest: there are not many venues through which women can learn about sex and sexuality with judgment-free and honest communication. (EIKAL, 116-17)

Now, if I were to summarise what I'd "learn" about sex from a lot of romance novels, it's that it's really important for a woman to be a virgin and/or never to have enjoyed sex prior to having sex with her hero and that when she does have sex for the first time, her hymen will probably be intact and be located half-way up her vagina. I would also learn that if a man is a hero, he can have had unprotected sex with thousands of women and never have contracted a sexually transmitted disease. That kind of information is neither helpful nor (in the case of the virgin or near-virgin heroines) "judgment-free".

I don't read romance novels for the sex: in fact, I prefer romances which don't include much detail about the sex the protagonists have, because it can make me feel as though I've been forced to invade their privacy.

I know other people feel very differently about this, and I know that many people feel their sex-lives have benefitted from reading romance. However, when advocates of romance novels stress their sex-positive aspects, they're not speaking for me.